Hominid Species Time Line

Page 9

Australopithicus afarensis

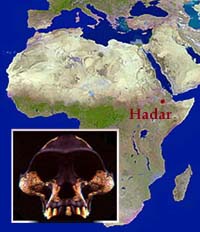

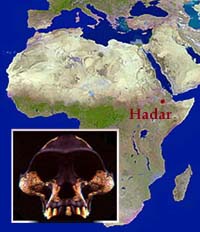

Australopithicus afarensis (“southern ape from Afar”) lived from approximately 3.8 to 2.7 million years ago along the northern Rift valley of east Africa, and perhaps even earlier. The first specimens were discovered near Hadar in Ethiopia by an expedition led by Donald Johanson in 1974.

Australopithicus afarensis (“southern ape from Afar”) lived from approximately 3.8 to 2.7 million years ago along the northern Rift valley of east Africa, and perhaps even earlier. The first specimens were discovered near Hadar in Ethiopia by an expedition led by Donald Johanson in 1974.

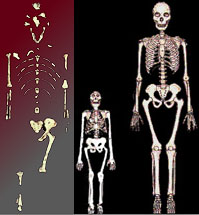

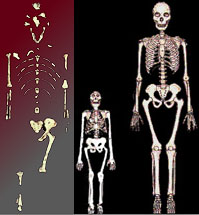

Fragments of 320 individuals of Australopithicus afarensis have been discovered, including a remarkably complete skeleton of an adult female (nick- named "Lucy") shown above and to the right. Her skeleton has provided a wealth of information about this species, some of it quite surprising. The illustration on the right above shows "Lucy" in comparison with a modern human female. She was only about 3 feet, 8 inches tall. In subsequent expeditions, a fairly complete male skull was found (AL 444-2, and, in 2000, a remarkably complete skeleton of a three-year old nursing infant, with face, hands, feet, knee joints, rib cage and shoulder bones intact.

DIK-1 Selam — the Dikika baby

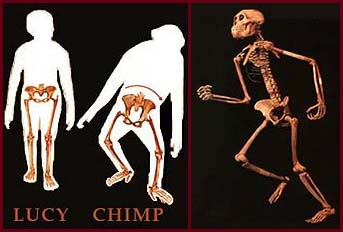

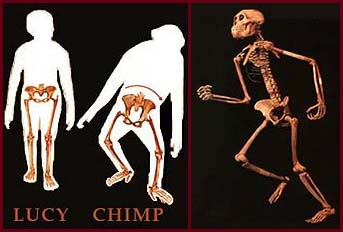

In terms of overall body size, brain size and skull shape, "Lucy," the female of the species, resembles a chimpanzee. However, A. afarensis has many human-like characteristics. For example, the way the hip joint and pelvis articulate indicates that "Lucy" walked upright like a human, not like a chimp. This discovery over 30 years ago revised previous ideas of hominid development and proved that upright posture and bipedalism long preceded the development of what we would recognize as human intelligence and other “human” characteristics. On the left is a reconstruction of Lucy's full skeleton. Note also that Lucy’s pelvic bones are adapted for bipedal walking, both in terms of how the hips attach and in its overall structure. That adaptation to support upright walking was significant later on, because it also decreased the size of the pelvic opening. Once hominid brains had increased in size significantly, it meant that hominid females had to give birth to large-brained (large-headed) infants. Birthing thus became a difficult and dangerous process to both mother and infant, and it drove additional changes in our ancestors and their relatives.

In terms of overall body size, brain size and skull shape, "Lucy," the female of the species, resembles a chimpanzee. However, A. afarensis has many human-like characteristics. For example, the way the hip joint and pelvis articulate indicates that "Lucy" walked upright like a human, not like a chimp. This discovery over 30 years ago revised previous ideas of hominid development and proved that upright posture and bipedalism long preceded the development of what we would recognize as human intelligence and other “human” characteristics. On the left is a reconstruction of Lucy's full skeleton. Note also that Lucy’s pelvic bones are adapted for bipedal walking, both in terms of how the hips attach and in its overall structure. That adaptation to support upright walking was significant later on, because it also decreased the size of the pelvic opening. Once hominid brains had increased in size significantly, it meant that hominid females had to give birth to large-brained (large-headed) infants. Birthing thus became a difficult and dangerous process to both mother and infant, and it drove additional changes in our ancestors and their relatives.

While A. afarensis walked upright like a modern human, they had long arms. The ratio of upper arm bone (humerus) to upper leg bone (femur) in A. afarensis is virtually the same as that of a Chimpanzee — 95%. The ratio of upper arm to upper leg in a modern human is around 70%. This suggests Lucy’s species were still adapted to climbing trees.

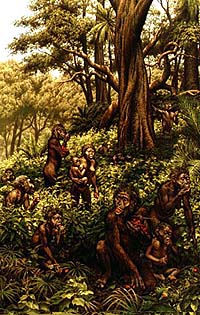

It is assumed that this species lived in small foraging social groups. While the climate of much of Africa was drying out during the period A. afarensis lived, the evidence suggests that this species lived in a wooded environment.

The teeth of A. afarensis are small and unspecialized, indicating a mixed, omnivorous diet of some soft and some tougher foods, such as fruits and nuts. The canines, highly developed in existing ape species, are small and undeveloped in this species, much as in human beings. Overall, the teeth are quite like those of modern humans. This species probably did not make or use tools or understand the use of fire, but we know nothing about their social behavior.

As in all early hominid species of which we have knowledge, sexual dimorphism is quite pronounced and was expressed in terms of body size: males were approximately twice as large (in bulk) as females and considerably taller (slightly over 5 feet tall). In mammals, this large size disparity between the sexes usually means that males compete aggressively for mating privileges with females. However, the large fighting canines found in male gorillas, chimps, and baboons are absent in A. afarensis, so their social behavior may have been quite different from these other primates.

Thus far, nearly all the remains of this species have been found in the Hadar region of Ethiopia, part of the Rift Valley of east Africa. However, hominid footprints 3.5 million years old have been found further south, at Laetoli in Tanzania, and it is speculated that they may have been made by this species.

Thus far, nearly all the remains of this species have been found in the Hadar region of Ethiopia, part of the Rift Valley of east Africa. However, hominid footprints 3.5 million years old have been found further south, at Laetoli in Tanzania, and it is speculated that they may have been made by this species.

For more information on Australopithicus afarensis see Donald Johanson and Maitland Edey, Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind (1981); or Donald Johanson and James Shreeve, Lucy's Child: The Discovery of a Human Ancestor (William Morrow & Co., New York: 1989), Donald Johanson, Lenora Johanson and Blake Edgar, Ancestors: In Search of Human Origins (Villard Books: New York, 1994).

References

Australopithecus afarensis on TalkOrigins.org

Australopithicus afarensis (“southern ape from Afar”) lived from approximately 3.8 to 2.7 million years ago along the northern Rift valley of east Africa, and perhaps even earlier. The first specimens were discovered near Hadar in Ethiopia by an expedition led by Donald Johanson in 1974.

Australopithicus afarensis (“southern ape from Afar”) lived from approximately 3.8 to 2.7 million years ago along the northern Rift valley of east Africa, and perhaps even earlier. The first specimens were discovered near Hadar in Ethiopia by an expedition led by Donald Johanson in 1974.

In terms of overall body size, brain size and skull shape, "Lucy," the female of the species, resembles a chimpanzee. However, A. afarensis has many human-like characteristics. For example, the way the hip joint and pelvis articulate indicates that "Lucy" walked upright like a human, not like a chimp. This discovery over 30 years ago revised previous ideas of hominid development and proved that upright posture and bipedalism long preceded the development of what we would recognize as human intelligence and other “human” characteristics. On the left is a reconstruction of Lucy's full skeleton. Note also that Lucy’s pelvic bones are adapted for bipedal walking, both in terms of how the hips attach and in its overall structure. That adaptation to support upright walking was significant later on, because it also decreased the size of the pelvic opening. Once hominid brains had increased in size significantly, it meant that hominid females had to give birth to large-brained (large-headed) infants. Birthing thus became a difficult and dangerous process to both mother and infant, and it drove additional changes in our ancestors and their relatives.

In terms of overall body size, brain size and skull shape, "Lucy," the female of the species, resembles a chimpanzee. However, A. afarensis has many human-like characteristics. For example, the way the hip joint and pelvis articulate indicates that "Lucy" walked upright like a human, not like a chimp. This discovery over 30 years ago revised previous ideas of hominid development and proved that upright posture and bipedalism long preceded the development of what we would recognize as human intelligence and other “human” characteristics. On the left is a reconstruction of Lucy's full skeleton. Note also that Lucy’s pelvic bones are adapted for bipedal walking, both in terms of how the hips attach and in its overall structure. That adaptation to support upright walking was significant later on, because it also decreased the size of the pelvic opening. Once hominid brains had increased in size significantly, it meant that hominid females had to give birth to large-brained (large-headed) infants. Birthing thus became a difficult and dangerous process to both mother and infant, and it drove additional changes in our ancestors and their relatives.

Thus far, nearly all the remains of this species have been found in the Hadar region of Ethiopia, part of the Rift Valley of east Africa. However, hominid footprints 3.5 million years old have been found further south, at Laetoli in Tanzania, and it is speculated that they may have been made by this species.

Thus far, nearly all the remains of this species have been found in the Hadar region of Ethiopia, part of the Rift Valley of east Africa. However, hominid footprints 3.5 million years old have been found further south, at Laetoli in Tanzania, and it is speculated that they may have been made by this species.